I’m Kathleen Lewis.

I’ve constructed this portfolio as part of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Professional and Technical Writing at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

Many of the documents on this site are instructional materials. As a part of my commitment to providing free or low-cost resources to students, all of the instructional materials are available for download. Briefly, you're welcome to modify or edit any of my assignment sheets for not-for-profit, educational use. For more details, please visit my License.

Thanks for visiting!

Final Final Reflection

Someone in the program once told me, and I don’t remember who it was, that the thing that happens is a complex thing, but the story gets simplified until it alone becomes part of your history. So this is the story of the thing that happened. I went back to school shortly after I turned 30 because I wanted to be a teacher. Later, I started thinking about being a professor instead. I counted up the years once, and I would probably be 40 before anyone called me ‘doctor.’ And yet …

I like to tell this story: my very first class as a brand-new grad student was in a hot, too-small classroom with a series of long, fold-out style tables arranged in an uneven parallelogram. We got the usual spiel, the welcome, the course overview, the goals, and a run-down of the major assignments in this course. This was Composition Theory. I was nine years-removed from my English degree and a summer past my history degree, and I worried that I was not prepared for grad school.

One of those major writing assignments in Comp Theory was a paper on a subfield in Composition. The choice of topics was virtually unlimited. I would discover soon that grad school assignments usually looked like this: write a fifteen to twenty-page paper about some aspect of the course that interests you. So the professor opened up the discussion to the class.

“What’s some aspect of the field you might like to write about?” he asked.

My classmates immediately start responding.ed I’ll only mention the worst ones because, strangely, the words that meant nothing were the ones that stuck in my brain.

“Feminist rhetorics.”

“Intertextuality.”

“Semiotics.”

“Pedagogical theory for L2 learners.”

“Rhetorical ecologies.”

This cool, twisting sensation swept over my body from shins up over my legs and across the top of my head. I felt my hairs stand on end. I sat there, silent and still. I am not a religious person, but I thought to myself, Oh, my god, what have I done? I glanced around the room to see if anyone else was panicking like me. If they were, they played it cool. At that point, I had paid for graduate school mostly out of my own pocket. I had quit my job and gone to work part-time for the next two to three years. I had taken this enormous risk, knowing the potential strain grad school may pose to my relationships, my mental health, and my finances.

I was trying to decide if I should just try to get a refund now. I didn’t have to be in grad school. I had had a career that I could go back to, and I already knew about the sunk cost fallacy.

When I tell this story, it’s my attempt at a humorous anecdote. Most recently, I told it in the Writing Center to two new grad students who were beginning the program as I was winding mine down. So in looking back at this moment, it was a laugh. Can you believe it? Even I felt far, far out of my comfort zone. You figure it out, I said. You learn to write better, faster, to study harder, to learn more, and discard the things you don’t need. I told them, we all have self-doubts and fears and insecurities. It’s okay if everyone sounds like a genius while you’re feeling totally out of your element.

I still felt it, that icy shift, that cold sweat breaking out over my body. I felt my tongue curled up behind my teeth so no one could see that traitorous muscle in my jaw tick. I saw those other students nod along with the topics while I tried not to show my panic.

I needed this moment. It was a slap in the face. It hit me like an icy splash of cold water in the midst of a 2 a.m. dark night of the soul. Later, I would realize that even if every single person in that room knew more than me, there wasn’t anything stopping me from learning it all.

I read everything. Every article. Every assignment. Every author that was mentioned in an aside in class. Every supplementary article or suggested additional text. Wikipedia. Comppile. Academic Search Complete. Popular media articles by academic writers. At some point, finally, I got to the point where I was able to figure out the difference between what I didn’t know and what I didn’t know I didn’t know.

I know that I haven’t taken the usual track through the program. It’s been nonfiction mostly, theory classes in rhetoric and composition, courses on pedagogy and instructional design. I have taken a wide variety of courses because I intend to teach these courses in the not-too-distant future. I’ve truly felt like I would do myself a disservice by specializing too early. That has meant perhaps not taking a few classes I would have enjoyed and instead learning about the things I would need to learn to be successful.

So now I’m left with reflecting on a situation that I’m still in the middle of. How can I explain what I know?

My portfolio is, in some ways, my reflective essay.

I learned HTML 1.0 on my own when I was twelve or thirteen. I had my own web page before Geocities was thing. I maintained it all through high school and part of college. Then Geocities disappeared, and my webpage was gone. I see the value in being able to control my own content online, the way it was many years ago, of being able to reach colleagues and students across the web, and about being able to decide how that media would reach them. I intend to continue to develop this website over the coming years with new projects I’m working on and to serve as a open access repository for my course materials.

This portfolio is coded by hand, using Atom.io. I first built this site as a combination project between Writing on the Web and face-to-face teaching Practicum. I incorporated the design elements — chunked text, responsive design, and accessibility — into a teaching portfolio with my teaching philosophy.

The colors are purple, a contrasting orange, and some shades of gray. I have never liked staring at a brightly-lit computer screen for long, so the colors are intentionally dark with high contrast elements for people like myself with light sensitivity issues. I have painstakingly tested the site for accessibility. The site is accessible to all types of colorblindness, including achromaticism. All of the links and images have titles. All of the headers have appropriate header tags for better reading with a screen reader. The pages adjust responsively for mobile and tablet users.

The writing assignments I chose because they show my progression from novice in the field to intermediate student to someone approaching a scholar in rhetoric and composition. My very first paper for this course I wrote on Keith Gilyard from Syracuse University. Gilyard is a pretty early adopter of rhetoric from English, bridging the gap between literary criticism and rhetorical theory. His students, two of whom I discuss in depth, applied the idea of right-to-language and the power of the African American voice into narrative. I found this appealing because, while this particular department has experienced the schism between English and Rhet/Comp, there is something especially powerful about using rhetoric and social criticism in literature.

My next assignment was my first critical theory paper, an historical look at the Official English movement and its effects on student learners. In the paper, I argue that the Official English movement is useless, that it’s born out of xenophobia, that failing to offer multilingual resources won’t help L2 learners learn English better or faster. We know this to be true. If anything, first-generation immigrants struggle with learning English throughout their lifetimes. Even Generation 1.5, those children who may have been born here but speak their parents’ language at home still struggle with literacy. Their children, the citizen children of immigrants and siblings of Generation 1.5, learn it. Despite educators and legislators arguing at cross-purposes about integrating immigrants and their children, we know that if we give the proper tools to people who want to learn the language, they will integrate more easily.

My online writing instruction paper is another example of a type of essay I wrote frequently in the program: the dreaded reflective essay. In this paper, I had just begun the Online Writing Instruction program. This was at the point in my master’s degree where I started developing a cohesive image of the type of instructor I wanted to be. I saw how the different pieces of the program started working together. I’ve always loved learning, but for the first time in a long time, maybe forever, I was starting to feel passionate about doing something about it.

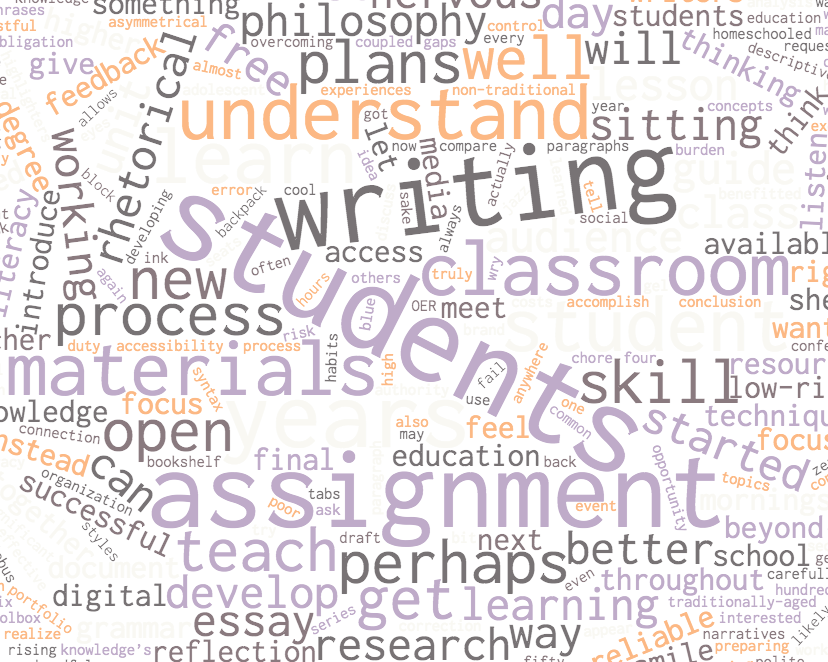

The final paper I chose for this portfolio was my dramatically named “Textbooks Cost Too Much and Everyone Knows It.” I’m still in the process of putting together an identity as an academic and a researcher. I know that it goes something like this: academic journals, textbooks, and educational resource materials are oftentimes far more expensive than they need to be. Excluding some rare, notable exceptions, the authors of said resources rarely profit off their creation. I’m passionate about making a university education accessible to anyone who can put in the work, and I don’t think that economics should be a barrier to getting a quality degree. In this essay, I combined the narrative essay with the research essay into a somewhat humorous, personal argument for more open access materials in higher ed.

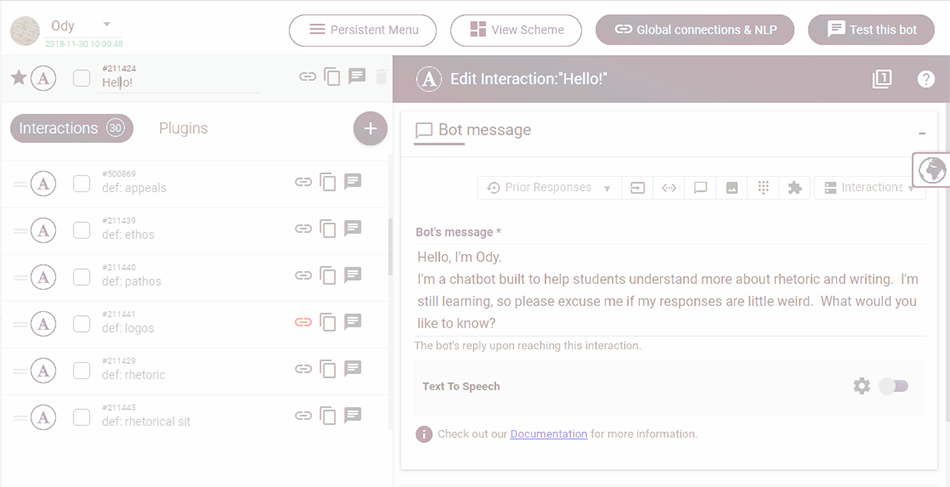

I designed Ody — gender-neutral name but vaguely Greek after Odysseus because it has undergone several acts of heroism to get onto the Internet — to answer students’ questions about rhetoric and composition. As of now, the chatbot can discuss about forty interactions, mostly about introductory-level rhetorical concepts and some questions about MLA format and citations. I started there because from my own, non-scientific observations, those (and due dates) are the two questions students asked me most often. The chatbot is not an artificial intelligence: Ody cannot learn. But I can use the chatbot as 24/7 resource for students to ask questions about topics I’ve covered in my courses. Since I created all of the answers, students can be assured that the chatbot knows what I want them to know.

When I assign my students a reflective essay, I tell them that this is not a course evaluation. I tell them that the reflective essay is a self-evaluation of their learning process. I tell them that writing about what they know helps reinforce the pathways in their brains so that can recall this knowledge more easily. I tell them to tell me what they did well, what they didn’t do so well on, what they’ve learned, and what they think they still need to learn.

And now for my last anecdote:

I realized about a year ago something about my mom. She used to say, “You can do anything, anything at all that you want to do. If you want to be a doctor or a psychologist or an astrophysicist, that’s what you should do. If you want to be a beach bum, be a beach bum. But you have to be the very best beach bum you can be.”

My mom must have said that hundreds of times when I was growing up. I didn’t live a perfect, suburban cookie-cutter lifestyle, either. There were certainly some tough times growing up in south Arkansas with blue collar parents. But there was never any doubt that she was proud of us. It’s a running gag, that the three of us kids are the smartest, most talented, most beautiful children who have ever lived. The joke is ubiquitously 21st century dark humor: my brother and sister were college dropouts, and I would have sold my dusty bachelor’s degree back any day of the week to be free from my student loans.

A few months before I got ready to walk for my master’s degree, it hit me—what a difference it must have made in my life to be told repeatedly how much I could accomplish if I actually put in the work. Even when I had lost all faith in myself, even when I doubted that I was smart enough or young enough to go back to school, that I could maintain a stable relationship with my partner, that I could work and teach and write and research, there was that 30-year-old part of me that knew I was only every standing in my own way.

I know that the master’s portfolio is supposed to be the culmination of the program, the race car made from the Erector Set, the haiku made from refrigerator magnets. But I can’t say that I’m finished. I’m almost halfway through school now.

Here’s what I’ve learned: not everyone has a partner who thinks it’s okay to take a decade out of the work force and put off putting down roots to pursue a degree (or seven). Not everyone has a parent who thinks they’re a rock star. Not everyone can find a job with flexible hours. Not everyone has the time or the resources or the energy that I do.

In the language of the academy, most contemporary college students will face a significant barrier to completing their education. Whether students have an ADA-covered disability, are temporarily or permanently place-bound, or experience an unexpected financial hardship, most students will have to make a decision about whether they can continue their education. As instructors, we could shrug our shoulders and move on from those who cannot, or we can build better courses that improve outcomes for those students whose living situations might make their education difficult or even impossible.

What I hoped I could do with this portfolio is continue developing it as a resource long after I have completed my degree. I want to have control of my own work. I want to know that the people who benefit from it are students and educators rather than monolithic textbook publishers. For students, I see the chatbot as an accessible communication tool that can speak for me when I am not available. For graduate students and new instructors, I would hope that my open access course materials would be out there for them to use freely. Even as I continue to do my research and write my own papers, I know that there are thousands of open access, peer reviewed journals to which I could choose to submit my work.

If not everyone has had my advantages, and I know how desperately hard I’ve worked for the last four years, I hope that I can alleviate some of the burdens that students face toward earning an education.